Have a sense that being ordained is really important and really precious and someone who has been able to remain ordained for so many years is something to rejoice in. If we have this attitude of appreciation for this whole lifestyle as a monk and nun, we will value our own ordination more.

Keeping Your Balance

By Ven Sangye Khadro

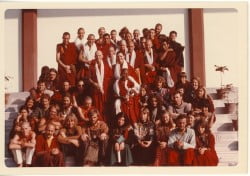

From a talk on, ‘How to Stay Ordained’ given at the pre-ordination course at Tushita Retreat Center, February 1999.

When we first become ordained and are very idealistic and enthusiastic-and don’t necessary know ourselves very well-it is hard to imagine that we would ever feel otherwise. It’s easy to feel that you would never change your mind, or have a different feeling. It’s helpful to remember that the mind is vast and things can arise that we are not prepared for and we are not aware of now.

You may have no doubts at all about being ordained, you may have no feeling at all of wanting to live a different lifestyle. But those kinds of thoughts and feelings could come up later. If that happens just accept them and don’t be surprised and don’t feel ashamed. It is my own and many other people’s experience that when certain types of thoughts and feelings coming up-what we would call negative, very unwholesome-we become upset with ourselves even to the point of beating ourselves up and feeling very bad. That’s not at all helpful and just makes more trouble. If you have a problem, feeling ashamed or angry on top of it just exaggerates it. It is important to have an attitude of acceptance of whatever comes up in the mind.

Remember that our minds have been around for beginningless time, and even though in this lifetime we haven’t done anything terrible, in our previous lives, we certainly have. We have done everything; we have done every kind of heinous crime. From this point of view, it’s not all surprising that even really negative thoughts can come, even though we have taken this step of becoming ordained and committing ourselves to the path of enlightenment. So if and when such thoughts, feelings, or states of mind arise, have the attitude of, “Oh this is some imprint from past lives because I have done things before which are quite unwholesome and it’s only normal that these kind of thoughts could come up.”

It’s also helpful not to be too tight and too strict. When we are in a situation like in India or Nepal or even a community of Sangha people, there is quite strong energy and a lot of support. It’s easier to be very strict in the vows and in your practice. But if you are in a situation-even in a Dharma center in the West-where there are no other monks or nuns or lamas, then it’s very difficult to maintain that same kind of strictness. It can happen that being overly concerned about keeping all the vows very strictly (which of course is a good thing to do) can sometimes be counter-productive. You might find yourself thinking, “Oh, that is just impossible, I can’t keep all my vows, maybe I’d better give up altogether.”

The Tibetans are generally quite flexible and easy-going about many things. Other cultures can be a lot more concerned about doing things strictly according to the rules, very ‘black and white’. When you talk to your lamas or to Tibetans about these things, they say, “Oh if you can’t do like this, then do it like that, it’s ok.” So I think it’s important to have that sort of flexibility. You have to find a balance between too tight or too loose; this will probably take time. But that’s an important aspect in being able to survive in ordination and being able to adapt in different situations. It’s not the way you practice when you are in India or in retreat or in the monastery. But you are not going to be able to be that way in all situations.

I have found it is really important to have an attitude of respect for those who have been ordained longer than I have. We are taught this but sometimes it can be difficult to practice it. When you are newly ordained and all fired up, you might look at some those who have been ordained longer and it might look like they are not keeping their vows very well; that they are sloppy or undisciplined. It can very easy for critical thoughts to come up. These are things to work on, don’t just suppress them.

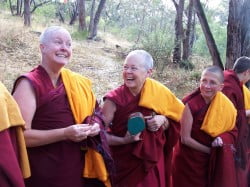

It is helpful to think that we don’t really know, like it says in the teachings, what a person’s motivation is. You may look at his behavior but we can’t be sure what his motivation is, we don’t have clairvoyance. We also may not know much about this person’s background. Some people are coming from rather rough backgrounds and compared to the way they were ten or twenty years ago, they may be like angels. They may be doing the best they can, even though they can’t keep all the vows perfectly. We should appreciate that even if they are not keeping all their vows, at least they are keeping some of their vows and that’s better than nothing. When you go back to the West it is very difficult, or even impossible to keep all the vows so strictly so we make adjustments to be able to survive as monks and nuns and to be able to keep going after years as a monk or nun. So it is important not to be critical and judgmental with regard to older Sangha and instead have a sense of appreciation that, at least, they are still ordained.

Maybe it’s arrogant for someone who is ordained only for a very short time to be judgmental of the older monks and nuns. Who knows where you are going to be ten years from now? What are you going to be like after so many years? Have a sense that being ordained is really important and really precious and someone who has been able to remain ordained for so many years is something to rejoice in. Just the fact that they are still in robes and still holding their vows is something so wonderful and so precious. If we have this attitude of appreciation for this whole lifestyle as a monk and nun, we will value our own ordination more.