Listening, Thinking, and Meditating

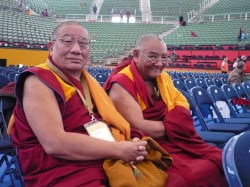

By Khensur Jampa Tegchok

Scripture states that first we need to abide in the ethical discipline of avoiding the ten destructive actions. On that basis, we listen to Dharma teachings and generate the wisdom of hearing. Then we think, check, analyze, and generate the wisdom of thinking. Finally, we meditate, by placing the mind single-pointedly on that meaning and thus generate the wisdom of meditation.

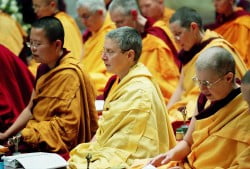

We need to listen well, and we must listen a lot. It is necessary to listen to teachings on one topic several times, not only once. Each time we hear, study, or read the teachings, we understand a little more and gain a broader view of them. We see the example of the great lamas who are alive today: they continuously go to listen to the teachings of their spiritual guides and read the scriptures. Without adequate hearing, we will not be able to think very well, and of course then we will not be able to meditate and it will be difficult to realize the Dharma and transform our mind.

What we call analytical or checking meditation is, in general, meditation. But within the three-hearing, thinking, and meditating-it is not termed meditation but thinking. In the three, meditation refers to putting the mind on a subject that has been clearly ascertained through contemplation. It is best to put the mind on the object single-pointedly, but that is not necessary. In the three, analytical meditation is included in thinking, because it is here that we decisively ascertain the meaning of a particular teaching and how to practice it.

Hearing, thinking and meditating are to be practiced in union. That is, we should apply ourselves to all three practices with regard to all of the essential topics, including impermanence, suffering, emptiness, selflessness, love, and compassion.

Analytical Meditation

How do we know we have gained the intended result from a given meditation? How much time should we spend on each meditation? How do we prevent the experiences we gain from deteriorating?

Although we have heard many teachings and may be enthusiastic to teach them to others, our mind is not subdued and our qualities are not developed. What is the difficulty? We have not gained experience from meditation and have not integrated our knowledge into our experience. In other words, we know a lot, but have not meditated on it properly. Merely knowing the teachings does not constitute analytical meditation. This does not produce the internal transformation that analytical meditation does. Analytical meditation is real meditation, important meditation. It is indispensable for generating realizations.

Occasionally, strong determination to be free from cyclic existence or strong faith in the Three Jewels may arise without having meditated a lot. This is not analytical meditation. From time to time we might think, “Cyclic existence is awful. I’m off to a cave in the mountains to meditate.” Or we may suddenly have a strong feeling of love for all sentient beings, but then it vanishes and we feel as we did before. Sometimes we may have a sense of the emptiness of inherent existence and think, “Now I’ve realized emptiness. This is fantastic!” But then the experience fades away and we think, “Oh no, I’ve lost the realization!” That also is not an experience arising from analytical meditation.

What are these experiences then? They are a form of belief or correct assumption. They are positive, but unstable. If they were inferential valid cognitions arising from thinking, they would not deteriorate quickly. When they go, do not be unhappy. They arose due to the blessing of the spiritual teacher, the Three Jewels, or from good imprints from past lives. We should try to make them firm. To do this, we should inspect the conditions which brought them about and try to reconstruct and maintain those conditions. That is, we should keep going and not allow them to degenerate. The way to make these sudden flashes of understanding stable is by familiarizing ourselves through analytical meditation.

An experience that arises from analytical meditation is valid and stable. It comes from having thought about something so that we understand it deeply. Analytical meditation does not mean repeating the words of the teachings to ourselves or going over the points of the teachings in a dry, academic way. It means thinking deeply about the Dharma and applying it to our own lives. It involves checking the teaching to see if it is logically consistent, if it describes our experience, if it is more realistic and beneficial than our usual way of thinking.

For example, a person new to the Dharma might hear about precious human life. She may have a strong experience regarding it, but subsequently this disappears. That strong feeling was an experience arisen from hearing and was easily lost. To make it stable, she should follow it with analytical meditation to gain experience arisen from thinking and contemplation. Then it will be more firm and transformative.

If we have heard many teachings and have a lot to explain to others, but do not familiarize ourselves with them and experience them, we might become immune or thick-skinned towards the Dharma. This means that when hearing teachings, we sit there thinking, “Yeah, I know, I know. I’ve heard all that before. Why doesn’t my teacher say something new and interesting?” Or we comment to ourselves, “This teacher could improve his or her way of speaking. Their way of delivery is so boring.”

We will know when we become immune to the Dharma. The mind becomes tougher and tougher. Even though we know a lot, instead of the mind being subdued, it become worse. If, having heard a lot and knowing a lot, the mind is becoming better-more flexible and open-minded, more receptive and appreciative of the teachings-we do not have the problem of being immune to Dharma. But when one’s mind becomes hard or proud like that, it is difficult to cure. Usually the way to make the mind good is to know what the Buddha taught. However, in this case, we know the meaning of the gradual path already, but our minds have become tough. We have become insensitive to the medicine. If a person has become immune to the Dharma, it is difficult for him or her to benefit even from a great master. Why? The spiritual master may use one reason to explain a certain point, but this student has studied a lot and thinks, “I know a better reason, I know more reasons.” It is difficult to benefit someone when his or her mind has become hard like this. Therefore, we should try to avoid becoming like that.

In Tibetan monasteries, when the pupils became clever the teacher says, “Be careful, you’re becoming immune to Dharma.” Those who do not know much have no danger of becoming immune, so there is no need to warn them. It is those who, knowing a little, become proud of their knowledge and proud of explaining it to others, who are in the greatest danger. They should be especially careful. When bad persons meet Dharma their minds can easily be made good. Before they did not know Dharma and did a lot of negative things. Then they meet Dharma and easily become good. But if we know a lot and our minds become immune to Dharma, it is very hard to change. The experience that arises from listening is a superficial understanding; we must practice analytical meditation on it. Even if we have only a little definite knowledge from analytical meditation, there is no danger of becoming immune to Dharma because the understanding has been made secure and tied to our experience.

A person who does not do analytical meditation might hear the statement that the aggregates are impermanent. She might think, “Yes, they are impermanent.” But that understanding can change so easily. She might meet someone who says they do not change moment by moment are thus are permanent, and she starts to wonder, “Maybe they are permanent, after all!” This situation arises because the person did not make her initial understanding firm by thinking about it deeply and from many angles in analytic meditation.

Someone may study a little Dharma and like it, but then meet a non-Buddhist teacher who says, “The Buddha’s teaching is wrong. If you devote yourself to my path, you will gain powers immediately.” The person then stops his Dharma practice and adopts another path. This is because he had not yet gained his own inner experience of the Dharma. His understanding was at the level of listening only, and he had not yet validated it and made it firm through contemplation and analytical meditation. When we have experience of the Dharma, whatever anyone says does not shake us. Our understanding is certain. We will not change easily.

The Buddha said we should not just take his word on anything, but check for the truth of his teaching by way of three analyses. These are likened to the three types of analysis made by those buying gold. First they check for the more obvious faults by rubbing the gold, then for less obvious ones by cutting it, and finally for the subtlest impurities by burning the gold. The Buddha said, “Check my teachings in this way too. See if they are true or not. Make your understanding firm through reasoning, and do not believe them on faith alone.” Lama Tsong Khapa also stressed this. This instruction gives us so much freedom. It is really marvelous advice.

How to do analytical meditation?

In daily life we often do analytical meditation. For example, when we are attached to a certain person, our basic assertion is, “He or she is wonderful!” Then we think of many reasons to prove that. She looks good, she is intelligent. He has a good mind, he is kind. She is interesting to listen to. He is marvelous to look at. With these reasons and many more we strengthen our feeling that this person is wonderful, and as a result, our attachment blossoms fully and we think we have to be with that person to be happy. There is no other way; we can’t bear to be without him or her. That is analytical meditation. If someone says otherwise, “He or she is unpleasant, not so attractive,” we do not listen to a word of it, because we are completely convinced. Analytical meditation is like this.

Sometimes we engage in analytical meditation on anger. We think such and such a person is so bad. We confirm this with various reasons, such as remembering that they hurt us or our friends in the past and they are talking behind our back now. We speculate on the harm they might do in future. We also back it up with quotes, “My friend said this person can’t be trusted,” and so on. The more reasons we have, the more convinced we become and the more impervious we are to another’s words pointing out that person’s good qualities.

This is how analytical meditation works in the case of disturbing attitudes. Similarly, we can use the same technique to reflect on Dharma topics for the purpose of increasing our constructive attitudes. Here we think of a particular topic, contemplate it repeatedly, use reasons to prove the various points. We should use whatever reasons and examples necessary to make the meditation topic clearer and more convincing, and keep the topic in mind without forgetting it. As we do so, the conclusion will arise in our mind as a stronger and stronger experience that we then hold in our mind single-pointedly. If this happens, it is a sign that our analytical meditation is yielding results.

For example, if we meditate on impermanence and death, we go through the three root points and the nine subsidiary points one by one. “Death is definite because everyone must die, because our lifespan is continuously decreasing and cannot increase. We will die without having done Dharma practice if we continue wasting our time.” We think about each point in depth, making examples from our lives, using reasons, applying it to our own experience. Thus the feeling dawns in our mind, “I must practice Dharma. This is really important.” When this feeling arises strongly, we cease analyzing and focus our mind on it as much as possible. This has a transformative effect on our mind. After that we can go on to meditate on the second root in the death meditation. Some people associate the term “analytical” with dry, intellectual verbiage and thus think analytical meditation is intellectualizing. This is not correct. By examining the steps of the path closely, with reasons and examples, and by applying it to our own lives, very strong experiences can arise that transform our minds.

It is possible that despite continuous meditation, our mind does not seem to be noticeably altering in a positive way or we get stuck in meditation or do not gain the experience from a particular meditation that our spiritual teacher said ought to come from it. In such cases, although we have not yet become immune to Dharma, there is a danger of that happening. To avoid it, we should temporarily stop the analytical meditation and focus on practices that purify karmic obscurations and accumulate positive potential for a week or two. It is very helpful to put more attention on practices such as making request prayers to the Three Jewels, prostrations, offerings, and so forth. It is also very effective to do guru yoga practices, such as Lama Tsong Khapa Guru Yoga, in which we recite the prayer requesting his inspiration. Then we can resume analytical meditation.

Through analytical meditation we gain certainty about our topic of meditation. This is the experience gained from contemplation. To gain certainty means to realize with a valid mind, and within the different types of valid mind, this refers to valid inference. The experience arising from hearing is an understanding that is merely able to echo what we have heard. That level of understanding is correct assumption or a belief that is true. Inference is much firmer; it is an incontrovertible understanding reached through sound reasoning.

When we do analytical meditation on a topic, we think over the various points, reflecting with effort on the reasons, the quotations, and the applications to our life. Applying it to our life means checking to what extent our life experiences confirm the points in the lamrim. It also means contemplating how to use the teachings to deal with situations and difficulties we encounter in our life. When, through such meditation, we develop positive thoughts, feelings, and outlooks, this is called “experience requiring effort.” At this stage, when we are thinking about the topic, the experience arises and is heartfelt, but when we stop thinking about the reasons, it fades. To make it firm, we need to habituate ourselves with the experience that was generated with effort, and by doing this, it will eventually become effortless. Whenever we think of the topic, the experience will automatically arise without doing analysis and is called “effortless experience.” For example, when someone is very attached to something, merely by remembering it the attachment arises automatically, without having to think about many reasons. Now our attachment is usually effortless while our Dharma understanding requires effort. However, by training our mind over time, the Dharma realizations of love, compassion, wisdom, and so on will become effortless, and it will take great effort to get angry or attached. Thus, first we do glance meditation to become familiar with the general layout of the topic. Then we apply effort to generate the experience of it. Finally, because our mind has become very familiar with the topic, the experience becomes effortless.

There are two basic types of meditation: stabilizing meditation to develop single-pointed concentration and analytical or checking meditation to develop deep understanding of the topics. Until higher levels of the path, these two types of meditation are done alternatively. We begin analytical meditation on the topics for the initial level practitioner: precious human life, impermanence and death, unfortunate realms of existence, refuge, and karma and its effects. Then we go on to do analytical meditation on the topics for the middle level practitioner: the four noble truths, the twelve links, and the three higher trainings. At the advanced level, analytical meditation is necessary for the meditations to generate the altruistic intention. When, through analytical meditation, we gain some understanding of a topic, we then focus on that understanding with stabilizing meditation. By eliminating distractions, the stabilizing meditation enables our mind to become more accustomed to the understanding we generate through analytical meditation.

Before beginning the actual analytical meditation, it is helpful to think, “Since beginningless time until the present my mind has been under the control of the disturbing attitudes-ignorance, attachment, anger, jealousy, pride, and so forth. They have made me act in harmful ways and have brought about the various difficulties I’ve experienced in cyclic existence. From now on, I must try conscientiously not to let my mind go under the control of the disturbing attitudes. I want to develop flexibility and firmness of mind so that I will be able to concentrate on the object of meditation without distraction or lethargy. I want to develop my good qualities, and since this depends on understanding and integrating the Buddha’s teachings into my being, I will put effort in this direction during this very meditation session.”

What we do during break time between sessions, when we are going about our daily activities, influences our meditation sessions and vice-versa. Therefore, during the break, it is advised to “close the doors of our sense faculties.” This means we should be aware of when to speak and what to say, so that we do not talk indiscriminately about things that stir up our disturbing attitudes or harm others. Similarly, we should not listen indiscriminately because this can stimulate many negative thoughts in our mind, and should avoid looking around indiscriminately at things that could incite our craving, anger, jealousy, and so forth. Before acting, it is wise to check whether the action is appropriate or not; and, if it is, we should do it with awareness. Eating and sleeping in moderation are important as well, and rising early in the morning is good. Whenever we do things to care for our body-eating, drinking, washing, dressing, sleeping, and so forth-we should think it is to bring well-being in the body and mind, which is necessary for meditation. In other words, we transform our motivation for these activities from one of self-indulgence and self-centered pleasure, to one of taking care of the body and mind so that we can use them to practice the path to enlightenment for the ultimate benefit of all sentient beings.

Colophon

(Teaching extracted from Transforming the Heart: The Buddhist Way to Joy and Courage. Reproduced with the kind permission of SNOW LION PUBLICATIONS.)