Meditation is the foundation of our religious practice; through it we can discover the Truth directly for ourselves. In meditation one learns how to accept oneself and the world as it is. Profound transformation becomes possible once we know things as they are.

Shasta Abbey—A Western Zen Monastic Community

Ven. Chantal Dekyi

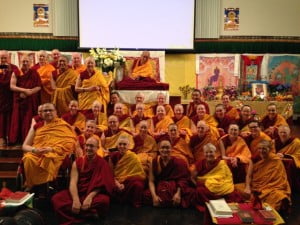

For over thirty years, Western monastics have been living and practicing together at a Zen monastery founded by a Westerner in northern California. In early June this year, three IMI nuns paid a visit to this well-established monastery, Shasta Abbey, where they encountered several distinctive features which have contributed to the enduring success of the community. This article is based on their talks with Rev. Meian, Rev. Meido, Rev. Daishin and Rev. Kodo and on a talk by Rev. Hubert.

In China and Japan, monasteries are traditionally located at the foot of mountains, and in that spirit, Shasta Abbey spreads across 16 acres of forested land at the foot of Mount Shasta. As with its geography, daily life at the abbey follows a carefully structured pattern, and that pattern forms an integral part of the practice of its residents, as those who live there attest.

Shasta Abbey was founded in 1970 by an Englishwoman and Zen Master, Rev. Master Jiyu-Kennet, who served as its abbess until her death five years ago. Her disciple, Rev. Master Eko Little, has succeeded her as abbot of Shasta Abbey.

Shasta Abbey is dedicated to the tradition of Soto Zen Buddhism and belongs to the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives, which was also founded by Master Jiyu-Kennet. Born in England in 1924, Rev. Master Jiyu-Kennet became a Buddhist at an early age, initially studying Theravada Buddhism. In 1962, after her master, the Reverend Keido Chisan Koho Zenji, invited her to his monastery in Japan, she began her training there. At the time it was unprecedented for a Western woman to join a monastery in Japan, and her training took place under extremely difficult conditions. However, she faced the difficulties in her path with an indomitable will, as rapidly becomes apparent from reading her biography, The Wild White Goose.

Master Jiyu-Kennet’s master, Koho Zenji, was the chief abbot of Sojiji, one of the two main temples of Soto Zen Buddhism in Japan and transmitted to her a form of empowerment known as Dharma Transmission. He later certified her as a Zen Master. After her master’s death, in 1969, Master Jiyu-Kennet left Japan to help bring Soto Zen Buddhism to the West.

Joining the Abbey

Shasta Abbey is open to lay guests, who are welcome to remain indefinitely, as long as they are willing to participate fully in the daily training schedule and abide by the rules for lay guests. There is a guesthouse for lay visitors and residents. About half of the monastery grounds are accessible to the public. The other half is reserved as a monastic enclosure. About 30 male and female monastics live at Shasta Abbey today.

Those who are interested in joining the monastic community may apply for postulancy. Applicants must be unmarried, have been unattached to a partner for at least two years, and be free of debt before beginning this period. Postulancy lasts at least one year, during which time the person follows the monks’ schedule. Postulants meditate and sleep in a long, narrow annex outside of the meditation hall.

If his or her wish to join the community is sustained and the community agrees, the postulant will enter a period as a novice that will last five or more years. Junior monks live in the meditation hall where only monks are permitted to enter. (In the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives, the term ‘monk’ is used for both male and female monastics, to signal a complete spiritual and functional equality between genders.)

Lay people meditate in the adjoining ceremony hall. All the monks’ belongings are stored in a small cupboard. At night, they roll out a sleeping mat at the place where they sit during the daytime meditation sessions.

After an indefinite period of a least five years, a novice may be ready to enter a phase of their training known as receiving spiritual transmission, in which they are introduced to the nature of their mind by their master. Once they have stabilized the knowledge of the transmission over a period of approximately three more years, they may be certified as masters themselves. While the focus for a junior monk is more on training themselves, senior monks are more active in teaching, leading meditation retreats and counseling. Some stay at the abbey, others go out to open their own temple from which to serve the lay community.

The Training

The origin of Zen Buddhism is said to be connected with the custom of Indian philosophers who sought to escape the subcontinent’s heat by dwelling in forests, spending their time in meditation and observance of religious ceremonies. The very name ‘Zen’ is the Japanese pronunciation of ‘Ch’an’, which itself is the Chinese phonetic transcription of the Sanskrit term ‘dhyana,’ meaning reflection or meditation.

The Zen tradition emphasizes practice over philosophy. The focus is on meditation, on keeping the moral precepts and on developing gratitude and compassion and expressing it in action. This training embodies the teachings that all beings have Buddha nature, even though it may be as yet unseen.

In this tradition, there is said to be a unity of training and enlightenment. The essence of their teaching is to demonstrate enlightenment; to make it manifest in one’s training.

“All the ways of being a monk, sitting, keeping the precepts, working with one’s mind, converting the self – the one that says ‘I don’t want to do it that way’ – finding the unborn, is the training,” says Rev. Meian.

Meditation

Meditation is the foundation of the practice at Shasta Abbey. “Zen teaching is to just sit but it is more than just sitting and yet it is just sitting,” says Rev. Master Jiyu-Kennet.

As explained in the abbey’s brochure:

“Meditation is the foundation of our religious practice; through it we can discover the Truth directly for ourselves. In meditation one learns how to accept oneself and the world as it is. Profound transformation becomes possible once we know things as they are.

“If I believe I am separate from everyone else, then I act selfishly to get what I want. If I know that within diversity, nothing is separate, then I already have all I need – for I am One with all things. Meditation enables us to discover the real nature of our own being.”

The precepts and the discipline

Everyone at the abbey is expected to abide by the rules of the community and of the Order and to participate in the daily training schedule, which provides a balance of sitting meditation, ritual and working meditation. That training is carefully regulated, with scheduled times for sitting meditation and religious service in the mornings and evenings. Six to seven hours of community work occupy the bulk of the day.

The abbey is a cloistered monastery. Postulants and novices up to six months are asked not to leave the premises, except for medical reasons. In general, residents are discouraged from leaving the premises. All trainees, both lay and ordained, abide by the sixteen precepts*, with celibacy replacing refraining from sexual misconduct for monastics.

There is much bowing at the abbey: bowing upon entering and leaving a room; bowing in gratitude; bowing at one another in recognition of the Buddha within. Each time their paths cross in the cloister – four, five, ten times a day – monks join palms at their heart. ‘Gassho,’ or bringing the palms together at the heart, is understood to be a way to center oneself and to express the unity in duality.

In a talk to a group attending a weekend introductory course, Rev. Hubert explains: “You hold yourself together, out of despair. You do Gassho continuously, offering the willingness to train.”

“The discipline, the forms, the schedule… It’s uncomfortable at first. Then it is worthwhile.” Rev. Daishin.

The classic example given is a snake that enters a bamboo stick, and from that understands better its nature as a snake. “We use form as training. The discipline supports the training. If you see it’s for your own good, it is liberating.

“You need the willingness to work on things and let go of opinions and ideas,” says one Shasta resident. “Training is a way of helping harmonize yourself and relating to others. Living in harmony is liberating. It’s a constant effort. It gets to you. You have to look at your ideas, your interest and what you are holding to. It keeps you in the present moment and lets you know when you are off.”

“That time in the zendo when I was a novice was a very precious time in my own training: I learnt how little space you need to live. How simply one could live; do just with what you need; be mindful of others; get up quietly; develop compassion.” Rev. Kodo says.

The day is carved up by the schedule. “You are having a good meditation. The bell rings, you have to get up from your seat and go on to the next thing. It leaves no time for wondering what you would like to do now. You learn how to let go of preferences,” says one resident. “Training is a letting go, over and over again. You give up everything, including your ideas about things. You give yourself over. Through the simplicity of this life, the bare bones of it, a cleaning process takes place.

“Keeping the rules is more than just the form. It becomes part of you. You get so used to it that it becomes natural. For example, when you go to town, after a long time without going out, it can be awkward or exciting. But then you start bowing to people just as you do here, and then people start bowing back to you….”

“We accord great value to mindfulness and compassion,” says Rev. Meian. “We help people to befriend the schedule and use it as a tool. Our master also encouraged us to keep our individuality. We are open to personal needs. We help people if they have a hard time and try to accommodate them if they cannot follow the schedule. There is latitude for individual training. The main point is keeping the spirit of the training.”

Life in Community

The practice of living with others in community harmoniously is an important part of the training.

“Didn’t the Buddha talk about community life a lot?” asks Rev. Daishin.

“I was really independent and attached to living by myself,” says one monk. “I had big fears about living in a community. On the other hand, I trusted that people here had the experience. And I found so much respect and caring about one another.

“Usually we have the idea that we have to talk a lot to be close to people. Actually, how much you get to know each other without words! Here, we don’t socialize. We don’t hide by saying ‘I am this or that.’ All social roles have been left outside. “Special friendships are discouraged in the community. When we are attached to someone, we tend to depend on him or her and become exclusive…Exclusive friendships are very linked to our likes and dislikes. I am looking for the company of this person, because she agrees with me. We are looking for somebody who sees things the same way as we do and then we comfort each other in that. Of course, there are people with whom we get along better than with others but it shouldn’t be set up in a discriminative way.

“When problems occur, we try to address the problem. People are encouraged to talk with each other, and solve problems. Lots of the time, we are the problem. Yet, we are all here for the same reasons. We know each other so well.”

Says Rev. Kodo: “For me, the turning point came from difficulty I had working with a senior person. We made some effort and sorted things out. We take refuge in each other. We trust in each other’s good intention, good will. So something opens up.”

“We are encouraged to communicate and the discipline helps us relate to each other in a more respectful way,” says one monk. “We do Gassho. We don’t yell at each other. It’s not like psychology, always expressing yourself. We are monks. We use the seniority system and respect grows naturally: Juniors respect seniors because they have held the vows longer. And seniors respect the juniors: they don’t push them around. If somebody is rude, I respond with courtesy. To train people, we show the example. We have to be polite. We have to be right here. We have to see the compassionate nature of the situation.

“Juniors might feel, ‘They are trying to make me miserable, make me do all this stuff.’ We are not here to make people hurt. They are already miserable without needing to do anything, without anybody having to manipulate anything.

“Our master used to say, ‘We want to do what is best for everyone.’ So we try to see how everybody can be helped, to see beyond the self.

“Just like tumbling stones rubbing against each other and polishing each other, living in the community, we polish each other,” says Rev. Daishin.

Work as a Practice

The teaching says that enlightenment and daily life are one and the same. Just as the precepts permeate life at Shasta, so does meditation. “Meditation is part of everything. We do normal things with the same understanding as we have when we sit on the cushion,” says one monk. “We keep the same awareness, the compassion, the bringing yourself back constantly, the mindfulness.”

Rev. Daishin says: “We need to do things. Buddha walked a lot. We use these aggregates for practice. Simple actions are grounding. Cleaning, cooking, washing clothes put us in touch with life. It keeps us coming back to something basic. Work keeps us in touch with practicality.”

* The 16 precepts are the Three Refuges, the Three Pure Precepts (refraining from evil, doing only good and doing good for others) and the Ten Great Precepts, which are I will not kill, I will not steal, I will not covet, I will not say that which is not true, I will not sell the wine of delusion – whether drink, drugs or the emotional appeal of delusive thinking – I will not speak against others, I will not be proud of myself and devalue others, I will not be miserly in giving either Dharma or wealth, I will not be angry and I will not defame the Three Treasures – that is, I will not deny the Buddha within myself or in others.