Since the pratimoksha vows are received from a preceptor, an instructor, and several members of the sangha, the rite of confession must also be carried out before members of the sangha-that is to say, a group of bhikshus.

Sojong-Purifying and Restoring our Vows

By Ven. Sangye Khadro

According to Geshe Jampa Tegchog in Monastic Rites, sojong-the ceremony for purifying and restoring our Pratimoksha vows-is one of the three duties of monks and nuns. (The other two are yarne, the summer retreat, and gaye, the ceremony at the conclusion of the summer retreat.)

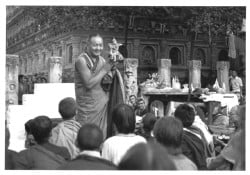

Geshe-la explained that in ancient times many bhikshus lived alone in their retreat places. They would gather together on sojong days to perform the ceremony. Guru Shakyamuni Buddha taught that sojong was extremely important to do, and in the past the bhikshus would wait with much expectation to perform the ceremony.

In the first years of being ordained, I didn’t really enjoy going to sojong. I have memories of standing out tall and slow in the midst of many small Tibetan monks, waiting outside the main temple in Dharamsala. When the signal came, the monks would rush in, do their three prostrations and rattle off the prayers at the speed of light, then run out as if the place was on fire. Not very dignified. Not much time to be mindful of the vows we were supposed to be purifying. And having to do all the prayers in Tibetan made it even more difficult.

Then I became a bhikshuni, and doing sojong with the Tibetans was no longer an option. Sometimes in retreat, when you have the luxury of all the time in the world to do whatever you want, I would do sojong on my own (which isn’t really a proper sojong, but still I felt it was beneficial to do). That’s when I started to enjoy sojong, because I read the prayers in English, so finally I could understand what I was saying!

But my interest in sojong really took off when I started doing it with other bhikshunis. That was in Deer Park, Wisconsin, while attending Geshe Sopa’s annual summer teachings. There are usually about 12-15 nuns (mostly western but a few Asian) who attend these teachings, and when there is a sufficient number of bhikshunis (at least four), we do sojong together. The novice nuns (getsulmas) join us, because ours is usually the only sojong happening at Deer Park. Ven Jampa Tsedroen, a German bhikshuni who is fluent in Tibetan, translated the sojong text for bhikshunis, with the guidance of her teacher, the late Geshe Thubten Ngawang. So in Deer Park we do the whole thing in English, and that way we can really understand the ritual.

It may come as a shock to some of you that there can be an all-nun sojong. This is something that probably never happened in Tibet or amongst the Tibetan refugees in India and Nepal. The reason for that is that there were never any bhikshunis in the Tibetan tradition. In the Chinese tradition, which has had bhikshunis continuously since the 4th century C.E., novice nuns should confess their vows to fully-ordained nuns, and novice monks should confess to fully-ordained monks. That makes sense, doesn’t it? But in Tibet, since there were no fully-ordained nuns, novice nuns did sojong along with the novice monks, confessing their vows before fully-ordained monks.

But the importance of doing sojong really hit home when I was doing retreat last year. I happened to read something in Pabongka Rinpoche’s Liberation in Our Hands that I never noticed before. It’s in the section on karma, and here’s the quote:

…if a bhikshu kills an animal he will incur both an innately wrongful act-the evil deed of destroying a life-and a transgression that violates a prohibited act-the precept against killing animals. To use the terminology of logic, the evil deed and the moral transgression are of one essence, though nominally distinct.

Here is a further point about an act that is both innately wrongful and was prohibited by the Buddha. We can completely rid ourselves of the element that constitutes an innate misdeed by applying the four counteracting forces. No matter how hard we try, we will not be able to remove the element that constitutes a moral transgression until we carry out a formal act of confession. By the same token, although we can purify ourselves of the moral transgression through confession, we can only expiate or purify ourselves of the innate misdeed by means of the four counteracting forces. Since the pratimoksha vows are received from a preceptor, an instructor, and several members of the sangha, the rite of confession must also be carried out before members of the sangha-that is to say, a group of bhikshus. (Liberation in Our Hands, Mahayana Sutra and Tantra edition, Part 2, p. 263. In the Wisdom edition, Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand, this section can be found on p. 457.)

So that means that if we do an action which is both an innate misdeed (i.e. is naturally non-virtuous) and a moral transgression (i.e. was prohibited the Buddha for those who take vows)- for example, killing an animal- there are two elements of non-virtue which need to be purified. We can purify only the element that constitutes an innate misdeed on our own by doing a purification practice such as the 35 Buddhas or Vajrasattva. But in order to purify the element that constitutes a moral transgression, we need to confess in front of a group of sangha, and that is what sojong is all about. So that means that for those of us who are ordained, it isn’t enough to just do purification on our own, we need to participate in sojong with other ordained people. Therefore, sojong is very important, otherwise it is very difficult to purify vows that we transgress.

That’s OK for those who live in places where sojong happens on a regular basis-e.g. Dharamsala, Kopan Monastery, Nalanda Monastery, Istituto Lama Tsong Khapa-but what about those of us who live in other places, where sojong rarely, if ever, happens? This question came up during a teaching on the getsul vows given by Choden Rinpoche in San Francisco last October. Choden Rinpoche said that the main sojong for getsuls is the part at the end of the getsul sojong when they go in threes before a fully-ordained monk, make three prostrations and recite some verses to declare their purity. And Rinpoche said that that can be done in front of any fully-ordained monk or nun, even if sojong isn’t happening. So as long as there is a bhikshu (or bhikshuni, in the case of novice nuns) in your area, you can go to them on sojong days and perform the sojong, even if you are just one novice.

However, before the getsul can go before the bhikshu/bhikshuni, they must first perform the rite of remedy (chir.chö) to purify their broken vows. This is the part of the sojong ritual which is recited by the getsuls when they first enter, starting with the words “All Buddhas and Bodhisattvas dwelling in the ten directions…” This can be done in front of one’s altar or an image of Buddha; by oneself or with other getsuls. And it is also necessary for the bhikshu/bhikshuni to do the rite of remedy (chir.chö) from their section of the sojong text, before accepting the getsul’s declaration of purity.

For bhikshus and bhikshunis, if there is an insufficient number to do the full sojong, the “sojong blessing” can be recited, in order to avoid the fault of not doing sojong. It is also possible to purify Pratimoksha vows by doing self-initiation.

And how does one know when it’s sojong day? You can find this out by checking a Tibetan calendar, such as the one available from Liberation Prison Project. And if any of you do not have a copy of the sojong text, check with other sangha members in your area if they have one you can photocopy, or contact your local IMI representative.

What happens at sojong? It begins with the fully-ordained monks or nuns reciting some verses to recall and confess any vows they may have broken, in order to purify them. This is what’s called the “rite of remedy” (chir.chö). Then the novices (getsuls) come in and do three prostrations and recite three times their rite of remedy. This is to confess any vows they have transgressed since the last sojong. Then all the sangha- those fully-ordained along with the novices-recite some prayers together:

* Praise of the Buddha by Way of his Twelve Deeds

* The Heart Sutra

* An offering of four tormas (to the Gurus and Three Jewels, to the Dharma Protectors, to sentient beings to whom we are karmically indebted, and to local spirits and protectors)

* Another praise to Lord Buddha, recited while making prostrations

The monk/nun presiding over the rite then recites the Sutra on Being Endowed with Morality. Then everyone recites the General Confession (“U-hu-la” prayer) together three times. This is followed by the actual sojong for the novices: they go in threes before a fully-ordained monk or nun, make three prostrations, then squat and recite three times a verse declaring their purity. They make three more prostrations, then they and the fully ordained monk or nun recite together the verse on pure morality.

That completes the sojong for the novices and they leave. Following that is the actual sojong for the fully-ordained monks or nuns. This mainly involves the presiding monk or nun reciting the Pratimoksha Sutra, which delineates the bhikshu/bhikshuni vows. Only those who have taken those vows are allowed to be present for that recitation. In the Tibetan tradition, it is common to recite the part of the sutra that covers the root vows, then some lines that merely mention the other categories of the vows. Otherwise, the recitation of the entire sutra can take one or two hours.

This is just a brief explanation of the sojong ceremony and its importance. I hope that it will inspire all of you to take more interest in doing sojong when you can. And I pray that the causes and conditions will come together to enable all monks and nuns everywhere to perform sojong on a regular basis, as well as yarne and gaye, the other two duties of monks and nuns.

Colophon

The information for this article was derived from teachings and advice from Choden Rinpoche, Geshe Jampa Tegchog, Geshe Lama Lhundrup, Geshe Ngawang Drakpa and Geshe Tega. I take responsibility and apologize for any misinterpretations or mistakes I may have made.