The Job of Ordained People

By Ven. Antonio Satta

It is important to know-and for those who do know, to remember-that desire does not start with becoming ordained. We may sometimes find ourselves wondering why we are so full of desire, as if the ordained life increased or brought desire.

Abstinence (for ordained people) and giving vent to desire (for lay people), if not accompanied by knowledge, can lead to irritation or anger and to dissatisfaction, respectively. So if we do not understand the negative consequences of desire, whether we are ordained or lay, we will always be frustrated. Desire does not have a social status.

The cause of desire is ‘pleasure.’ It is in dependence upon pleasure that desire arises. Many people believe that desire is the cause of pleasure, so they say “If I don’t desire it, how can I enjoy it?”

One of the so-called omnipresent mental factors is feeling. When the feeling is pleasant, that is ‘pleasure.’ When we experience pleasure, there arises a wish to experience it again; that is desire.

Pleasure does not always arise by experiencing the object directly. We may hear the description of something and experience pleasure in dependence upon that description, so we desire it. We may just hear the name of something and a feeling of pleasure arises, so again we desire it. If we observe carefully, we can see how pleasure precedes desire.

Desire means ‘wanting.’ When our desires are fulfilled, but we still feel empty and so we still want, we become dissatisfied. When we are dissatisfied and we wish to do something else or be somewhere else, that is boredom. When someone else gets the thing that we desire, we feel envious. When we obtain the thing that we want, then the fear of separation can arise. If the object is a person, the fear of losing him or her becomes jealousy. When, due to certain causes and conditions, we are separated from the object we like, a sense of loneliness can arise. When our desires are always unfulfilled, we can become irritated and angry. When our desires are constantly frustrated, we can become depressed. So when we look at the consequences of desire, we can see how bad it is. Desire is like a breeze that blows over the water, and the consequences of desire are like the huge waves that follow that initial breeze.

Buddha said that if there were another affliction as bad as desire or attachment, nirvana would have been impossible. If we ask ‘How do we control desire?’ or if we wonder how Buddha encouraged his followers to ‘cool’ desire, the answer is by controlling or cooling pleasure. It is pleasure that we need to learn how to handle.

How do we cool pleasure? With mindfulness. Mindfulness means neither to ignore nor to cling, but to acknowledge. When we don’t cling to what is pleasant, we stop the wish to re-experience it; we stop the desire for it.

By stopping the wish to re-experience pleasure are we denying pleasure? The answer is no, because when we are mindful of a pleasant feeling we are fully aware of it, so we fully experience it. When we are fully aware, fully mindful of something, we create the space that allows us not to identify with it, so we don’t become that thing. When we are mindful of pleasure, on the one hand we experience that pleasure fully, and on the other hand we have the opportunity to see where it can lead.

So what is the perfect, the best condition for training in the practice of mindfulness? The answer is simple: the ordained life. Why? Because the ordained life focuses on controlling the physical and verbal actions. As a result of that, one creates the conditions to withdraw the mind inside. When the mind is withdrawn, it can see, notice, be aware, hold its object, and does not forget what it is experiencing. There’s no distraction. That’s mindfulness. Buddha called the training in mindfulness ‘the path of purification.’ Why? Because by neither clinging to what is pleasant nor having aversion to what is unpleasant, we stop hopes and fears, desire and irritation, attachment and anger, like and dislike, good and bad, friend and enemy. That’s what the mind is purified of.

Buddha also said that training in the discipline of mindfulness is the best ornament, which makes the person spiritually attractive. That’s the reason why throughout the centuries the Sangha could enjoy financial and moral support. If we ask what the job of a monk or nun is, the answer is non-activity! Their job is to neither to cling to pleasure nor have aversion to pain.

Sometimes we find monks or nuns who do not know what they are supposed to do. They feel depressed if they find themselves uninterested in studying the scriptures. Of course, studying is important, but we must also understand that at some point we must look at our mind, and when we look at our mind it is not intellectual understanding that we need but mindfulness: the ability to be present and to look.

From the very beginning, Buddha emphasized both meditation and learning. The purpose of studying is to show us that there is an alternative to suffering. Meditation makes us understand suffering. As we know, Buddha taught suffering first. This, perhaps, may indicate that first we need to meditate, which means generating an awareness, through mindfulness, of our present condition and then study to see what the alternative to our present condition could be. Without understanding our present condition, studying has little meaning. We may become simply idealistic, aspiring to something like a nice place to be.

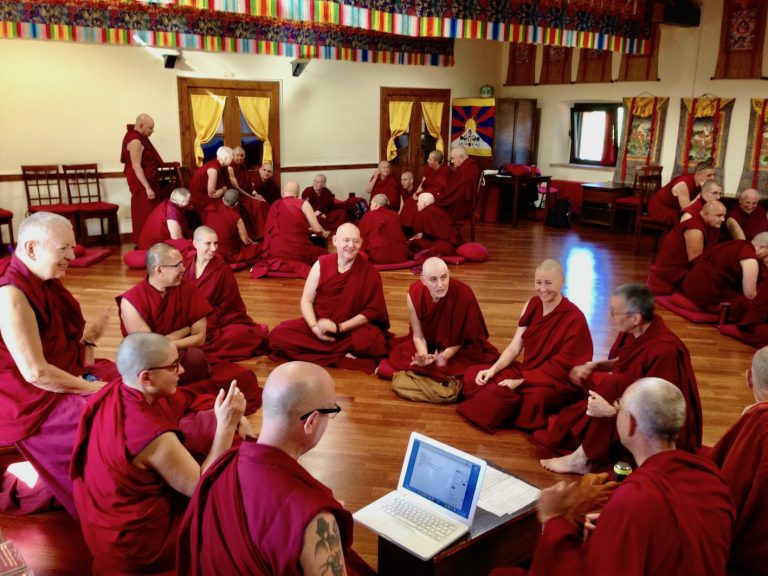

What I’m trying to say is that we do need both meditation and study, but it is with meditation that we really begin. And if the path begins with meditation (looking at the mind with mindfulness), who has the best conditions? As I said earlier, the ordained ones. The Sangha: those who have the right conditions to withdraw the mind inside.

“Because the ordained life focuses on controlling the physical and verbal actions. As a result of that, one creates the conditions to withdraw the mind inside. When the mind is withdrawn, it can see, notice, be aware, hold its object, and does not forget what it is experiencing. There’s no distraction.”